A command line terminal with an ssh command entered

You will learn:

Quick Quiz: Try each of the items below to see how quick quizzes work.

The CyberLab is on online facility located in various data centers and other locations across the Internet. It operates by remote access using:

Instructions are provided on videos for a variety of specifics under different operating systems and software tools. We will focus on one particular set operating under Mac OS-X. Similar tools under other operating systems are demonstrated in the CyberLab videos available at all.net under "Courses / Webinars".

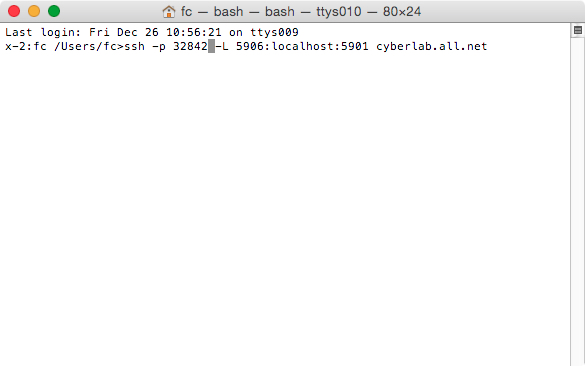

Secure shell under OS-X and other operating environments is operated by a command line from athe Unix "shell", typically, but not always, a program called bash. Normal users see this through a terminal interface. An exmaple is shown here:

From this point forward, we will present command and results in text rather than graphical format. For example, the previous picture will be represnted as follows:

Last login: Fri Dec 26 10:56:21 on ttys009 x-2:fc /Users/fc>ssh -p 32842 -L 5906:localhost:5901 cyberlab.all.net

Boldface is used to represent user input while output is not boldfaced. Italics is used for comments.

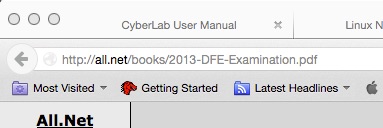

Computers in the CyberLab and many other places differentiate between UPPER and lower case, digits (e.g., 0, 1) and letters that look like them (e.g., O, l), and generally require that inputs match exactly to expectations in order to be acted upon as desired. While spelling errors in human readable text (such as this one) may be intrepreted reasonably by humans, computers will produce results that may be unporedictable and/or undesirable, in some cases in the extreme. For that reason, it is often easier and more effective to "cut and paste" complex sequences than to try to type them. This is done by use of the mouse and/or keyboard in different ways on different systems. We assume you have this figured out for your system. As an example, if we ask you to enter the URL http://all.net/books/2013-DFE-Examination.pdf into your browser, and instead, you enter http://all.net/books/2O13-DFE-Examination.pdf you may get very different answers. To make sure you do it right, try copying and pasting the URL into the browser window where URLs go. Here's what it should look like...

This may take you several tries. Make sure you copy the URL after the "URL" and not the one with the link you can click on. Make sure you paste it into the right place in your browser - where URLs go, and not where searches go. Get this right before we contine on.

Now, let's try another one. Put this URL into your browser:

Again, be careful to put it in the URL area and not the search area. After you succeed, remember this technique for future use.

Quick Quiz: Pick from the selections below:

Secure shell (ssh) is a program that runs on one computer to connect it to other computers over encrypted end-to-end connections. Encrypted connections are intended to prevent others from being able to read the content communicated while the ssh protocols also provide assurance of non-alteration of the content in transit, if properly used. Note that intent does not always meet reality, but for ssh it usually does. End-to-end encryption means that, between the user's "end" of the communication and the server's "end" of the communicaiton, everything going back and forth is encrypted and authenticated. That means that computers in the middle of the communication cannot alter or observe the content. However,

If improperly used, man-in-the-middle attacks can be carried out so that a computer between the end points may decrypt, read, alter, and reencrypt the communications in one or both directions.

Using ssh does not protect against denial of services, does not provide attribution of the people at the endpoints, does not provide transparency, does not provide information on custody, and so forth.

Using encryption does not protect the endpoints from being exploited, including breaking in and altering the programs used to provide the encryption, reading and writing at the ends of the "secure" ssh communicaitons "tunnel", stealing the encryption keys, or anything else that exploits the endpoints.

When you use ssh there may be covert channels in that, for example, your typing patterns as to timing and sequences used at the start, end, middle, when using particular applications, and so forth, may be used to tell what you are communicating, which programs you are using, what commands you are typing, who is using the system, and so forth.

In the CyberLab, we only use ssh to provide for encryption of the content and integrity of the message stream. The purpose is to make it hard for a user to accidentally allow an attack in the cyberlab to spread outside of the CyberLab. We have no secrets, and we don't track who uses what when or anything else of that sort. We just want to grant access to authorized parties at authorized times. As such, ssh provides the tunnel between the user's mouse, keyboard, and screen and the virtual mouse, computer, and screen of the CyberLab area they are accessing.

Secure shell is typically run by issuing commands like this:

fc>ssh adam.all.net The authenticity of host 'adam.all.net (72.167.3.128)' can't be established. DSA key fingerprint is 62:5e:b9:fd:3a:70:eb:37:99:e9:12:e3:d9:3f:4e:6c. Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)? yes Warning: Permanently added 'adam.all.net' (DSA) to the list of known hosts. fc@adam.all.net's password: Welcome to Ubuntu 12.04.4 LTS (GNU/Linux 3.8.0-35-generic i686) * Documentation: https://help.ubuntu.com/ New release '14.04.1 LTS' available. Run 'do-release-upgrade' to upgrade to it. Last login: Fri Dec 26 05:58:45 2014 from 74-95-10-169-sfba.hfc.comcastbusiness.net XXX:fc /home/fc>

In this case, ssh was told to open an encrypted communication channel with the remote computer with an IP address (72.167.3.128) associated with the name adam.all.net and it did so, logging into the remote computer. Unless told otherwise, ssh assumes the user identity (name) on the remote computer is the same as on the local computer. But if we wanted to login as another user, we would be able to specify it as we will see below.

Since there was no previous communication with a computer of this name the protocol warns the user that this might be any computer, and provides the "DSA key fingerprint" for the remote computer. You can check this against a known value (if you have it) to verify that this is the computer you intended to talk to, and this is the mechanism used to try to reduce or eliinate man-in-the-middle attacks. From now on, after the "yes" answer is given, unless the remote DSA key fingerprint changes or the user removes the key from their local key listing, no warning will be given and access will be assumed acceptable.

Next, the user is prompted for a password. If the user ID and password are valid, the user is logged in and the session proceeds as if the user's local terminal were a local terminal on the remote computer. They can type another command and it will be executed on the remote computer.

However, in the CyberLab, this is not what happens...

Quick Quiz: Pick from the selections below:

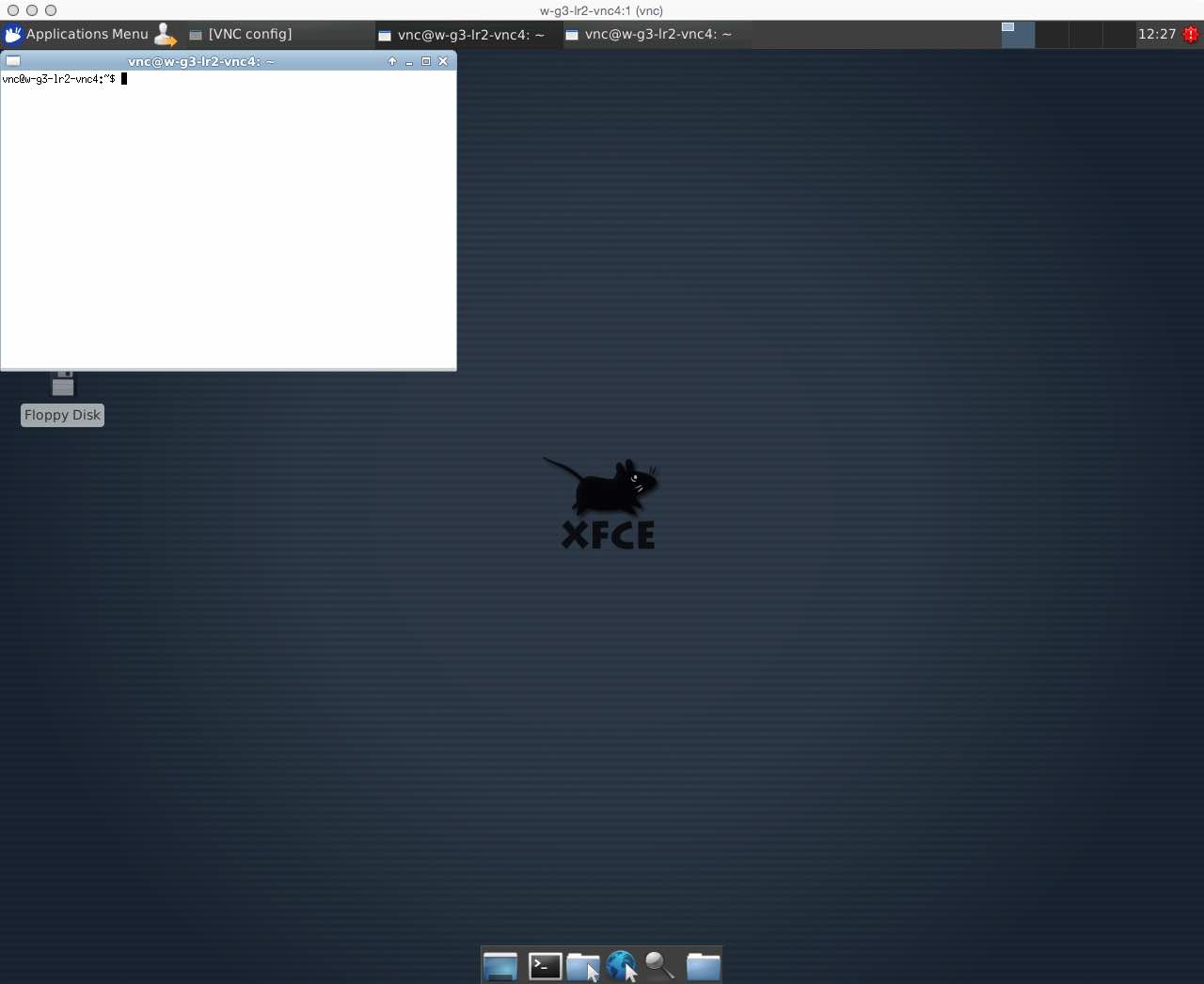

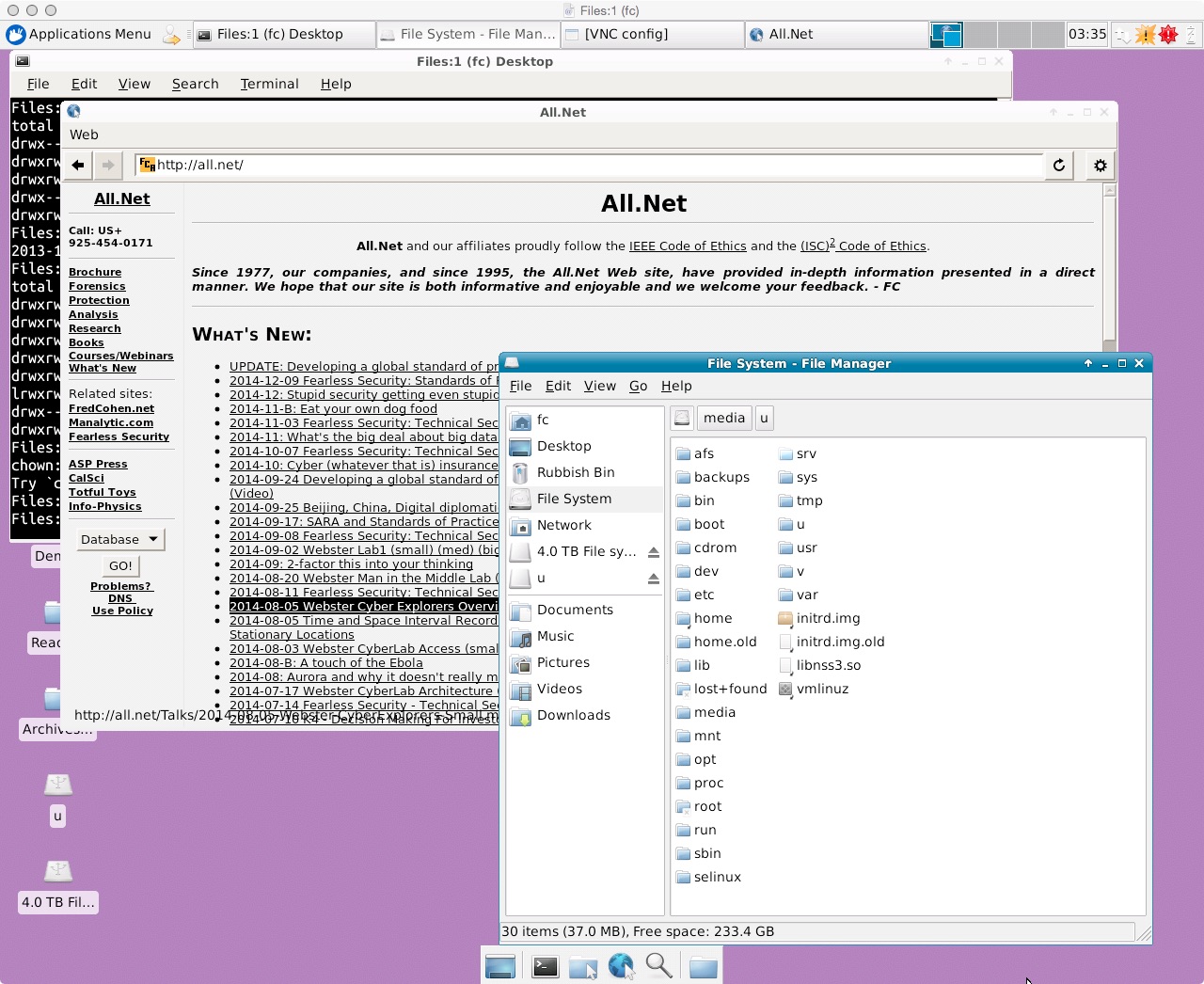

VNC makes it appear as if there is a display screen, mouse, and keyboard for a remote computer on your local computer. Here is an example of a VNC display of a remote computer on a local computer:

As you can see, it looks just like a local computer screen and mouse and keyboard actions in the windows work pretty mush as if the computer were the one you were using locally. If you want to see the picture at its full size, use your Web browser to view the picture - but it is reduced here so it doesn't take up your whole screen.

Quick Quiz: Pick the best answer:

While VNC is a very useful protocol, it is inefficient in many ways, and perhaps more importantly, it is easily broken into for alteration and surveillance purposes, and has poor quality authentication. As a matter of principal, the CyberLab doesn't want to run such insecure mechanisms between distant computers.

However, ssh has a few features that weren't mentioned before. One of those features is that it allows other protocols to be "tunneled" through the ssh secure tunnel between computers. That means that, for example, you can tunnel VNC through ssh tunnels and gain the advantages of VNC and the advantages of ssh in combination. Secure (end-to-end encrypted and autenticated) VNC sessions (over ssh) is how the CyberLab operates for remote access.

It turns out that the example depicted above runs VNC over ssh to do its work. The way this works is a bit complicated, and would take about a page to explain. But since the CyberLab is built to be easy to use, you don't have to know the details to be able to use it. We just like to tell you so you understand it better. So if you like, you can skip the next paragraph and remain ignorant of the details. But don't skip too many or you will miss the part about how you can use ssh to transfer files.

VNC uses transmission control protocol (TCP) ports (sessions between endpoints with specific bit sequences in datagrams sent between computers are used to encode the specific sessions so input and output on one side of the connection are connected to the right programs on the other side of the connection and vice versa). These ports are associated with specific positive integers in the range from 0 through 65535. VNC usually uses ports starting at 5901 and working their way up to as far as they need to go to accomodate the sessions in use. In the case of the CyberLab, we typically use anywhere from 3 to 30 ports, different ports for different virtual machines.

In order for ssh to "tunnel" protocols through encrypted sessions, it provides the means to remap ports on the initiating machine to different ports on the receiving machine so that if a local port is in use, a different port can be used for the secure shell connection on the other side. For example, ssh normally runs from a user port to server port 22. But in order for VNC running on port 5901 to pass through the tunnel, it has to actually travel over port 22. So en router, port 5901 gets tunneled through port 22, and ssh provides the ability to make it appear on the local computer on any port desired (for example port 5902 if there is another VNC session to another remote computer already running on port 5901). That means you can have as many different VNC sessions running through different ssh tunnels to as many other computers as you like (up to 65535 of them) by assigning each a different local port to connect to the remote port.

As it turns out, you can do this on both ends of the ssh connection. So that's what the CyberLab does. When you login remotely with ssh, on the local end, it maps the session into port 5901 (unless you specify otherwise). On the remote side, it maps the port into the port number of the VNC session running on the virtual machine running on the physcal machine associated with your user identity for the reserved time period for your lab session. It does this by executing a man-in-the-middle attack on the ssh protocol. You come into a ssh session on a computer that decrypts the session, remaps it to the proper internal session on a different IP address and port, remaps the VMC tunnel from the one you used to come in to the one necessary to work on the internal side of the CyberLab based on your user ID, password, and the port you used, and re-encrypts the session and tunnel into the virtual machine within the CyberLab that you use to work in.

Quick Quiz: Pick the best answer:

All of this is transparent to you, the user, so you don't have to worry about the various DSA keys for the various virtual machines in the various physical machines at the various IP addresses within the various CyberLab facilities. It all appears as one and the same thing to you. You just see a VNC session to a remote computer on your screen and use it as if nothing happened between you and it.

In theory, we could watch all the sessions going back and forth, alter traffic, and so forth. And anyone breaking into the computers performing these tasks could also do that. Of course we could also do that on the endpoints within the CyberLab. So:

A short note on user privacy

Those of us who run the CyberLab don't care about what you do in it, we really only care about keeping it working. We try to make sure the computers are "secure", but not because we care about your privacy. We protect the mechanisms because we don't want to have to keep fixing them. The ideal system to us is one that we never have to do anything to. It just runs itself. Then we can focus on what we are interested in, which is developing new and better experiments and class experiences.

Note carefully that last part. We don't seek to store your information after your session. It get's lost as the virtual disk for the virtual machine gets recreated for the next session. That and the fact that you only access the CyberLab by keyboard and mouse actions and screen viewing makes it pretty useless as a repository for secrets.

Quick Quiz:

Of course you might like to be able to store some things for some time longer within the CyberLab. That's why we support secure file transfer (sftp).

The sftp protocol and software uses ssh as a tunnel to store and retrieve files to and from file servers. Like VNC, sftp transfers files through encrypted authenticated tunnels. It has all the limitations and issues as ssh in terms of protection by cryptography. However, the sftp system in the CyberLab has a few interesting added features. They are (1) the diode and (2) the internal file server.

The diode

The diode is a way to get content into the CyberLab. You send files into the server, they disappear from the external file server and appear on the internal file server. The files go in but they don't come out and they don't stay around, so you cannot get them back or have someone else retrieve them. Here's what you type from your computer:

sftp myfile cyberlab.all.net:

Don't forget the ':' at the end... You will have to enter your user ID and password at that point. Some time later, within the CyberLab, the file (myfile) will appear on the internal file server and you or anyone else in the CyberLab can get it from there.

To transfer more than one file, list the files one after another. To transfer directories, use the "-r" switch as follows:

sftp -r mydirectory cyberlab.all.net:

The '-r' switch indicates "recursive" transfer - in that it will recursively send all files and directories, their files and directories, and so forth.

For more information on things you can use ssh and sftp for, you might want to try using the "man" command under Unix-like systems or look for manuals on the Web by searching the Web for further details.

Quick Quiz: Note - there can be more than one right answer to many of our questions...

The internal file server

Within the CyberLab, you will have access to a virtual machine (VM). You will be the superuser (e.g., 'root') on the computer and able to do anything you like to it. This includes wiping out all the files including the operating system and accounting files, crashing the VM, and then having to wait till your next session to have a clean try at it.

Since your storage in the VM is wiped out between sessions, you might want to save your critical work between sessions. That's why internal to the CyberLab, we have a file server. The file server uses the file transfer protocol (FTP) to allow any CyberLab user to place their files on the server and retrieve them at a later time.

To use ftp, you typically have a session like this:

vnc@w-g3-lr2-vnc6:~$ ftp 192.168.2.254 Connected to 192.168.2.254. 220 Welcome to the cyberlab FTP. Name (192.168.2.254:vnc): anonymous 331 Please specify the password. Password: No password was entered - press enter 230 Login successful. Remote system type is UNIX. Using binary mode to transfer files.

The "ftp" command runs a program called ftp that initiates a session between the computer it is running on and the computer specified on the command line. In this case, the computer is identified by the Internet Protocol (IP) address 192.168.2.254 which is an example of an internal address used within the CyberLab for the FTP server.

ftp> passive Passive mode on.

Passive mode FTP makes certain that all communications sessions to and from the FTP server are started from the local computer you are running 'ftp' on. This is important in the CyberLab because all of the real and virtual computers communicating to the FTP server do so using network address translation (NAT). The actual addresses used to communicate may differ, and in order for the server to return information, it has to rely on the sessions started by the initiating computer.

ftp> dir 227 Entering Passive Mode (192,168,2,254,210,99). 150 Here comes the directory listing. drwxrwx-wx 4 0 0 4096 Sep 18 14:40 files 226 Directory send OK.

A "dir" (directory) command can be used to see what is on the FTP server. In this case, there is one directory called "files". This directory is protected "drwxrwx-wx" and owned by user 0 and group 0 (as the listing shows). The proteciton settings (rwx for the owner, rwx for the group, and wx by others) identify that the root user and group can read, write, and execute (enter) the directory. However, other users (including "anonymous") can only write and enter the directory. There is no "root" login to the FTP server, so don't bother trying to guess passwords. That means that the ONLY users are "anonymous" with no password required, and that you, as an anonymous user, can put things into the directory, read them back out, delete them, but you cannot see what is in the directory. Since this is the only place you or others can put files in the FTP server, once you or they put files there, you and they cannot see what they were called. Nobody can.

ftp> cd files 250 Directory successfully changed. ftp> put NOTES local: NOTES remote: NOTES 227 Entering Passive Mode (192,168,2,254,207,219). 150 Ok to send data. 226 Transfer complete. 472 bytes sent in 0.01 secs (35.6 kB/s) ftp> dir 227 Entering Passive Mode (192,168,2,254,126,163). 150 Here comes the directory listing. 226 Transfer done (but failed to open directory).

To use the "files" directory, this example did a "cd" to change directory to "files". Then it did "put NOTES" to put (copy) the file NOTES from the current directory on the local computer to the file names "NOTES" in the FTP server under the "files" directory. Next, a "dir" command was used to list the files in the directory on the FTP server, and as you can see, nothing was shown.

ftp> get NOTES local: NOTES remote: NOTES 227 Entering Passive Mode (192,168,2,254,134,54). 150 Opening BINARY mode data connection for NOTES (472 bytes). 226 Transfer complete. 472 bytes received in 0.00 secs (515.6 kB/s) ftp> quit 221 Goodbye. vnc@w-g3-lr2-vnc6:~$

To prove that NOTES was there, we did a "get NOTES" to get (copy) the remote file NOTES from the current directory on the file server to the current directory on the computer we ran 'ftp' from. Note that it overwrote the previous "NOTES" file on the computer running the "Ftp" program from. Finally we "quit" FTP and returned to a command prompt.

Quick Quiz:

To do the right thing, I deleted this file later on...

vnc@w-g3-lr2-vnc6:~$ ftp 192.168.2.254 Connected to 192.168.2.254. 220 Welcome to the cyberlab FTP. Name (192.168.2.254:vnc): anonymous 331 Please specify the password. Password: I pressed the Enter key 230 Login successful. Remote system type is UNIX. Using binary mode to transfer files. ftp> cd files 250 Directory successfully changed. ftp> passive Passive mode on. ftp> del NOTES 250 Delete operation successful. ftp> quit 221 Goodbye. vnc@w-g3-lr2-vnc6:~$

You can also make directories in the FTP server (under the "files" directory), and their contents will be visible once you enter that directory. For example:

vnc@w-g3-lr2-vnc6:~$ ftp 192.168.2.254 Connected to 192.168.2.254. 220 Welcome to the cyberlab FTP. Name (192.168.2.254:vnc): anonymous 331 Please specify the password. Password: I pressed the Enter key here 230 Login successful. Remote system type is UNIX. Using binary mode to transfer files. ftp> passive Passive mode on. ftp> cd files 250 Directory successfully changed. ftp> mkdir test 257 "/files/test" created ftp> cd test 250 Directory successfully changed. ftp> put NOTES test local: NOTES remote: test 227 Entering Passive Mode (192,168,2,254,251,173). 150 Ok to send data. 226 Transfer complete. 472 bytes sent in 0.00 secs (2164.0 kB/s) ftp> ls 227 Entering Passive Mode (192,168,2,254,97,116). 150 Here comes the directory listing. -rw-r--r-- 1 120 65534 472 Dec 27 07:45 test 226 Directory send OK. ftp> cd .. 250 Directory successfully changed. ftp> mdel test mdel test/test? y 250 Delete operation successful. ftp>

Note that I cleaned up after myself by removing the directory and its contents.

Quick Quiz:

A few subtleties remain:

If you forget the name of a file or directory, we cannot help you. You will not be able to get the file or directory back unless you can guess or recall the name. The FTP server is slow to respond to such attempts, so that in order to guess all of the filenames of 3 characters long will take more than the hours hours you have for a session. To guess all the 4-character filenames would take more than a year. So don't bother. Remember the names you use. HOWEVER, when you create a directory under "files" in the FTP server, things stored in that directory will, by default, be visible to you. So once you get into a subdirectory, you will normally be able to see what you put there.

Anyone in the CyberLab can read, write, delete, or overwrite any files or directories on the FTP server. No user ID or password is required. The only protection you have is the name of the files and directories you place there. But as it turns out, this is as good as any other protection scheme out there. Consider this. Suppose you put all your files in a directory with a name the same as what you might choose for a user ID followed by a password? As an example, John.Smith-My23Pas45W823oRd. Anyone who could access this would have to know your user ID and password, which is all that would be required if you had a user ID and password for the FTP server in the first place. Because they can only try them so quickly, they will run out of time before guessing enough times unless you use a weak directory name, like "1" or "0".

The sessions with FTP are not encrypted. This would be a problem is you were using the Internet do do things. But you are not. The CyberLab separates virtual machines (VMs) so you (hopefully) cannot see the traffic from other VMs. On the other hand, since you can also use the FTP server from VMs within your VM, you can do experiments with sniffing FTP traffic and extracting filenames and contents just as you could watch user IDs and passwords and session content on the Internet if it were used this way.

The CyberLab FTP server has limited space. It stores files across sessions, but if you store big things there, it will run out of space. To fix this, we empty it every once in a while, typically at the end of a semester, but not always. So don't use a lot of space, and if everyone else also doesn't use a lot of space, you will all be OK. HOWEVER... Since everything in the CyberLab is anonymous and we don't even try to track it, one bad actor can spoil the whole bunch. Just like the rest of the Internet, the CyberLab is a shared resource. Share it wisely or you will ruin it for everyone.

Finally, you may recall that when you use sftp to put files into the CyberLab, they disappear from your external account and appear (eventually) within the CyberLab. They appear on the FTP server under the "files" directory using the name you gave them. If somneone else uses the same name either inbound through the diode or within the FTP server from inside the CyberLab, the last one in is the one that will be available. So name them carefully, don't forget their names, and don't send too much.

Quick Quiz:

In the CyberLab, we create user IDs (UIDs) and passwords for access. They are typically long and arbitrary strings like CaBAFQBpaq2AE6vpXDgEvbwrPzr0LFqr or whatever we happen to produce that day at that time. We create files with lists of these UIDs and password pairs (yes - they are plaintext password files containing UIDs and passwords). We provide sets of these to professors for use by the students in their classes. We don't particularly remember what professor gets what sets of these, and if they want more of them, we send more of them. We don't know who gets what UIDs and passwords and we don't try to find out.

We send UIDs and passwords out, the professors hand them out, and we provide each one with a finite number of sessions they can reserve using our time slot reservation system. Typically, we provide them 10 at a time. Each UID and password gets 10 time slots (give or take) for use as available. If they run out and the professor wants them to have more, we give the professor more UIDs and passwords. Since nothing is stored in the VMs and the FTP server uses whatever you want for filenames, changing your UID and password has no effect other than making you use a different pair to login, do resevations, etc. when one runs out.

To get your UID and password, you have to contact your professor. We don't intervene, we don't have anything to do with it, and we don't know how your professor chose to allocate the UIDs and passwords we provided. To get more they only have to ask us for more - up to a point. We do have finite resources, and eventually we will run out. In any given semester, we currently support only up to 64,000 or so UIDs.

At the end of the semester, we delete all of the existing UIDs and create a new set of them. We don't spend any time or effort trying to remember or forget old UIDs and passwords, we just delete what's there, create a new set, send them to professors who ask, and move forward from there.

In summary, ask your professor. If you are a professor, ask us.

Quick Quiz:

Time slots in the CyberLab are allocated as they are requested. First come - first served. You go to the Web site provided by your professor and use the UID and/or Password provided to access the reservation system. In the reservation system, you request a time slot from the set made available to you. Those are all of the time slots still available as of the time you make the request, so if you don't see a good one, you should have tried sooner. Since they are finite and all of the ones we have are made avilable, there are no more to provide than the ones you see. It's a competitive world and the early bird gets the worm.

Quick Quiz:

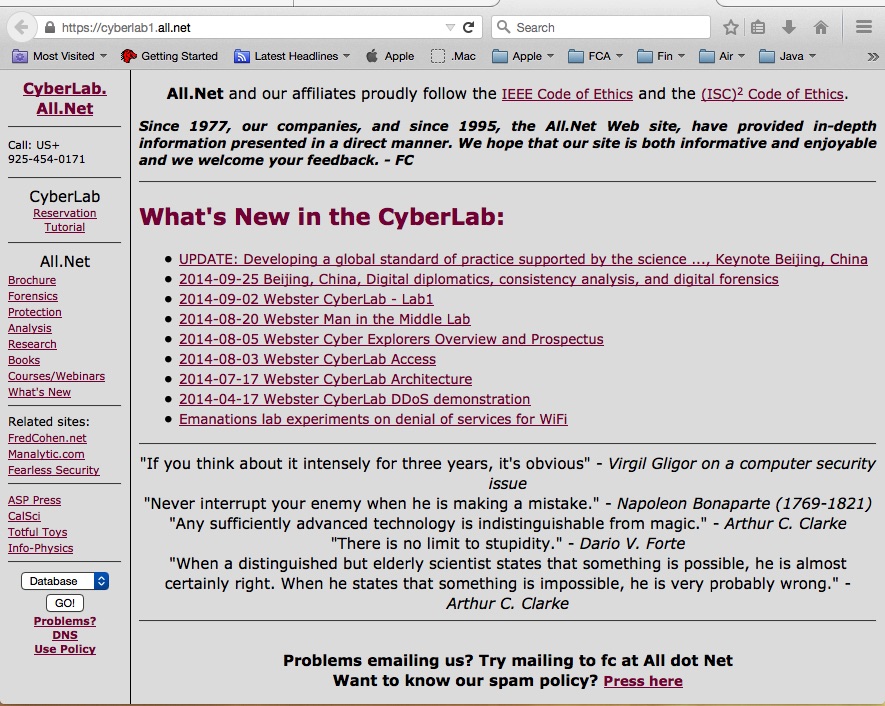

Here's how it works. Use your Web browser and enter cyberlab1.all.net into the URL area. You should see something like this:

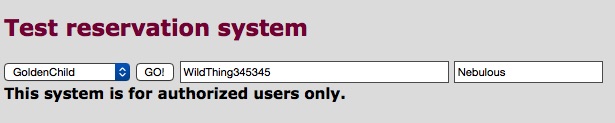

When you select "Reservation" from the left-hand frame (column), you will see something like this:

Enter the authenticating information you got from your professor into the form (yours will be different from that shown above), press the "GO!" button, and you should see something like this:

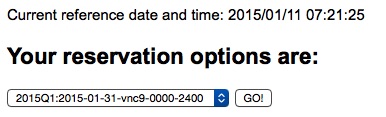

Note that the current time in the CyberLab (which might be in a different time zone or offset from yours) is shown at the top of the screen. When you select a time slot for your reservation, use the one appropriate understanding that the CyberLab is offset relative to the time of day and date based on what timeone you are in.

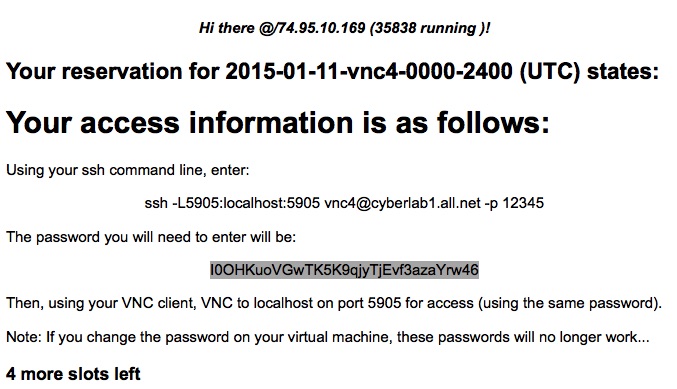

Select a time and date convenient to your usage, and please don't choose one that is already passed (unless you have a time macine and can go back and use it). Once you select a time slot and press "GO!", you should see a screen like this:

DO NOT DO A SAVE-AS!!! Copy and paste this into a text window! Don't wait till later or refresh the page. The page will not be displayed again by the Web browser. If you try to do a Save-As or something like that, it will likely fail because most browsers reload the page when doing a save-as. That will both fail to work properly and produce a different output that may be a deception.

Quick Quiz:

Note a few things:

How it works

When you reserve a time slot, the reservation system gives you session details. Typically, these will include the details you need to access the CyberLab for your reserved time slot. Here's how it works:

At the beginning of the semester, we generate all of the time slots that will ever exist for that semester. Each one is associated with a VM and time window. We generate all of the session details at that time. These session details include IP addresses, ssh ports, VNC ports, user IDs, and passwords.

The time slot information is then put into the reservation system for granting access to authorized users. This process produces a set of instructions in HyperText Markup Language (HTML) format associated with each time slot, with the name of the entry being the description of the time slot.

Dates and times are identified as a four-digit year (YYYY) followed by a dash (-) followed by a two digit month (MM) followed by a dash (-) followed by a two-digit day (DD) followed by a dash (-) followed by a two-digit hour (HH) followed by a dash (-) followed by a two-digit minute (mm) followed by a dash (-) followed by a two-digit second (ss). Thus 2020-10-12-08-15-13 corresponds to October 12, 2020 ar 8:15 and 13 seconds, AM. The reason for this format is that it sorts very easily, either numerically or by string sorting, producing the resulting dates and time in proper time sequence. If you leave off things at the end (like seconds, minutes, etc.) it still sorts crrectly so that 2019-09 comes before 2019-09-23 comes after 2019-09-22-59 and so forth. This makes human and programmed understanding easier when you get used to it.

At any given time, there may be any number of different VMs available for user reservation. Within the CyberLab, VMs are rebooted at the end of their pre-reserved prior time slot. The VMs do not retain state information across reboots, so when the VM restarts, it is loaded with the details for the next time slot. Since all of the details are generated at the beginning of the semester, if the computers containing the VMs crash, when they reboot, they will again continue operating according to the schedule, picking up where they previously left off. If a VM gets rebooted by the user, it will reboot to the original configuration for the current time slot, allowing the user to reenter with a clean slate. The reservation system only provides the details for the reserved time slot and does not communicate at all with the computers in the CyberLab.

When you reserve a time slot, the entry for that time slot (the HTML formatted output) is removed from the pool of available time slots, sent to you via the Web interface, and you see it on your screen. The count of avaiable time slots for the UID reserving the slot is then reduced by one. If it reaches 0, the UID is deleted from the reservation system and is no longer available for reservations. Sometimes, a reservation will fail to go through, likely because between the time you saw the potential reservation slot and the time you requested it, someone else reserved it. In that case you will be told of the problem and you will have to pick another slot.

The reservation information is only shown

once! When you see it, you should copy and paste it from your Web browser

into a file in your system so you can use it when your time slot

arrives. Otherwise, neither you nor anyone else will ever be able to

use the time slot you reserved.

Do not "save-as" or otherwise try to download the

reservation! The act of doing a save-as or similar acts tends to

do another download, which will fail, losing the data on your

screen. Copy and paste from the browser window into another file for

later use!

When your time slot arrives, you can then use the information from your reservation to access the CyberLab VM you reserved. You do this by following the directions, which may be different from what you see here.

To be clear, your UID and/or Password are used for getting reservations and sending files into the CyberLab through the diode. They persist over the duration of your class or until you use all of the avilable time slots. They are NOT used to access the CyberLab itself. The information from the reservation system is used to access the CyberLab and changes for each time slot.

Quick Quiz:

For the purpose of this tutorial, but it may be different for your actual use, suppose you get instructions like this when you get your information from the professor:

Suppose you want to put a file called TestFile into the CyberLab FTP server for use in your work there. Here is what you would do:

> cp TestFile 8dc08a4073ba7957b653ef17ac8bc87f.TestFile > scp -p 23742 8dc08a4073ba7957b653ef17ac8bc87f.TestFile 8dc08a4073ba7957b653ef17ac8bc87f@diode.all.net: Password: Enter your password e6bd40d94d202cd10a4617084fd10083 here >

That's it. Some time later, the file 8dc08a4073ba7957b653ef17ac8bc87f.TestFile will show up in the FTP server, and since nobody else will likely be able to guess or use the same name, there it will sit untill you use it from within the CyberLab.

Suppose you want to reserve a time slot for using the CyberLab. Here's what you would do:

Quick Quiz:

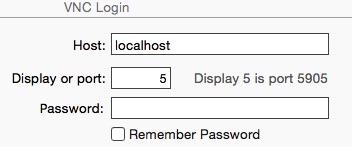

Once ssh is operating, you should be able to use VNC to enter the CyberLab. For OSX, we used "Chicken" (the new verison of Chicken of the VNC) as shown here. Note that the port (5) corresponds to 5905 (VNC ports stypically start at 5901) and that localhost reflects the use of ssh as detailed earlier.

Once this runs, you will have to enter the password again for VNC access, or you might decide to save it formultiple entries during the same slot. Here's what it look like once you are in: