Chapter

8

SECURITY

AND PLANNING IN THE COMPUTER SYSTEM LIFE CYCLE

Like other aspects of

information processing systems, security is most effective and efficient

if planned and managed throughout a computer system's life cycle,

from initial planning, through design, implementation, and operation,

to disposal.65 Many security-relevant

events and analyses occur during a system's life. This chapter explains

the relationship among them and how they fit together.66

It also discusses the important role of security planning in helping

to ensure that security issues are addressed comprehensively.

This chapter examines:

- system security plans,

- the components of

the computer system life cycle,

- the benefits of integrating

security into the computer system life cycle, and

- techniques for addressing

security in the life cycle

8.1 Computer Security

Act Issues for Federal Systems

Planning is used to help

ensure that security is addressed in a comprehensive manner throughout

a system's life cycle. For federal systems, the Computer Security

Act of 1987 set forth a statuary requirement for the preparation

of computer security plans for all sensitive systems.67

The intent and spirit of the Act is to improve computer security

in the federal government, not to create paperwork. In keeping with

this intent, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and NIST

have guided agencies toward a planning process that emphasizes good

planning and management of computer security within an agency and

for each computer system. As emphasized in this chapter, computer

security management should be a part of computer systems

management. The benefit of having a distinct computer security plan

is to ensure that computer security is not overlooked.

|

"The

purpose of the system security plan is to provide a basic

overview of the security and privacy requirements of the subject

system and the agency's plan for meeting those requirements.

The system security plan may also be viewed as documentation

of the structured process of planning adequate, cost-effective

security protection for a system."

-OMB Bulletin

90-08

|

The act required the

submission of plans to NIST and the National Security Agency (NSA)

for review and comment, a process which has been complemented. Current

guidance on implementing the Act requires agencies to obtain independent

review of computer security plans. This review may be internal or

external, as deemed appropriate by the agency.

A "typical"

plan briefly describes the important security considerations for

the system and provides references to more detailed documents, such

as system security plans, contingency plans, training programs,

accreditation statements, incident handling plans, or audit results.

This enables the plan to be used as a management tool without requiring

repetition of existing documents. For smaller systems, the addresses

specific vulnerabilities or other information that could compromise

the system, it should be kept private. It also has to be kept up-to-date.

8.2 Benefits of Integrating

Security in the Computer System Life Cycle

| Different

people can provide security input throughout the life cycle

of a system, including the accrediting official, data users,

systems users, and system technical staff. |

Although a computer security

plan can be developed for a system at any point in the life cycle,

the recommended approach is to draw up the plan at the beginning

of the computer system life cycle. Security, like other aspects

of a computer system, is best managed if planned for throughout

the computer system life cycle. It has been a tenet of the computer

community that it costs ten times more to add a feature in a system

after it has been designed than to include the feature in

the system at the initial design phase. The principal reason for

implementing security during a system's development is that it is

more difficult to implement it later (as is usually reflected in

the higher cost of doing so). It also tends to disrupt ongoing operations.

Security also needs to

be incorporated into the later phases of the computer system life

cycle to help ensure that security keeps up with changes in the

system's environment, technology, procedures, and personnel. It

also ensures that security is considered in system upgrades, including

the purchase of new components or the design of new modules. Adding

new security controls to a system after a security breach, mishap,

or audit can lead to haphazard security that can be more expensive

and less effective that security that is already integrated into

the system. It can also significantly degrade system performance.

Of course, it is virtually impossible to anticipate the whole array

of problems that may arise during a system's lifetime. Therefore,

it is generally useful to update the computer security plan at least

at the end of each phase in the life cycle and after each re-accreditation.

For many systems, it may be useful to update the plan more often.

Life cycle management

also helps document security-relevant decisions, in addition to

helping assure management that security is fully considered in all

phases. This documentation benefits system management officials

as well as oversight and independent audit groups. System management

personnel use documentation as a self-check reminder of why decisions

were made so that the impact of changes in the environment can be

more easily assessed. Oversight and independent audit groups use

the documentation in their reviews to verify that system management

has done an adequate job and to highlight areas where security may

have been overlooked. This includes examining whether the documentation

accurately reflects how the system is actually being operated.

Within the federal government,

the Computer Security Act of 1987 and its implementing instructions

provide specific requirements for computer security plans. These

plans are a form of documentation that helps ensure that security

is considered not only during system design and development but

also throughout the rest of the life cycle. Plans can also be used

to be sure that requirements of Appendix III to OMB Circular A-130,

as well as other applicable requirements, have been addressed.

8.3 Overview of the

Computer System Life Cycle

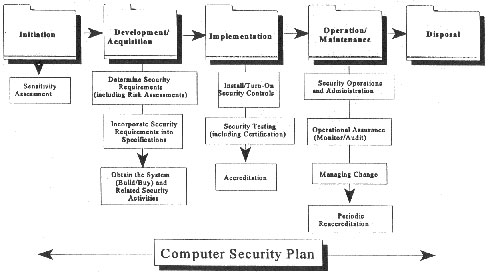

There are many models

for the computer system life cycle but most contain five basic phases,

as pictured in Figure 8.1.

- Initiation.

During the initiation phase, the need for a system is expressed

and the purpose of the system is documented.

- Development/Acquisition.

During this phase the system is designed, purchased, programmed,

developed, or otherwise constructed. This phase often consists

of other defined cycles, such as the system development cycle

or the acquisition cycle

.

- Implementation.

After initial system testing, the system is installed or fielded.

- Operation/Maintenance.

During this phase the system performs its work. The system is

almost always modified by the addition of hardware and software

and by numerous other events.

- Disposal. The

computer system is disposed of once the transition to a new computer

system is completed.

| Many

different "life cycles" are associated with computer

systems, including the system development, acquisition, and

information life cycles. |

Each phase can apply

to an entire system, a new component or module, or a system upgrade.

As with other aspects of systems management, the level of detail

and analysis for each activity described here is determined by many

factors including size, complexity, system cost, and sensitivity.

Many people find the

concept of a computer system life cycle confusing because many cycles

occur within the broad framework of the entire computer system

life cycle. For example, an organization could develop a system,

using a system development life cycle. During the system's

life, the organization might purchase new components, using the

acquisition life cycle.

Moreover, the computer

system life cycle itself is merely one component of other life cycles.

For example, consider the information life cycle. Normally

information, such as personnel data, is used much longer than the

life of one computer system. If an employee works for an organization

for thirty years and collects retirement for another twenty, the

employee's automated personnel record will probably pass through

many different organizational computer systems owned by the company.

In addition, parts of the information will also be used in other

computer systems, such as those of the Internal Revenue Service

and the Social Security Administration.

8.4 Security Activities

in the Computer System Life Cycle68

This section reviews

the security activities that arise in each stage of the computer

system life cycle. (See Figure 8.1.)

8.4.1 Initiation

The conceptual and early

design process of a system involves the discovery of a need for

a new system or enhancements to an existing system; early ideas

as to system characteristics and proposed functionality; brainstorming

sessions on architectural, performance, or functional system aspects;

and environmental, financial, political, or other constraints. At

the same time, the basic security aspects of a system should

be developed along with the early system design. This can be done

through a sensitivity assessment.

|

Security

in the System Life Cycle

The

life cycle process described in this chapter consists of

five separate phases. Security issues are present in each.

Figure

8.1

|

| The

definition of sensitive is often misconstrued. Sensitive

is synonymous with important or valuable. Some

data is sensitive because it must be kept confidential. Much

more data, however, is sensitive because its integrity or availability

must be assured. The Computer Security Act and OMB Circular

A-130 clearly state that information is sensitive if its unauthorized

disclosure, modification (i.e., loss of integrity), or unavailability

would harm the agency. In general, the more important a system

is to the mission of the agency, the more sensitive it is. |

8.4.1.1 Conducting a

Sensitivity Assessment

A sensitivity assessment

looks at the sensitivity of both the information to be processed

and the system itself. The assessment should consider legal implications,

organization policy (including federal and agency policy if a federal

system), and the functional needs of the system. Sensitivity is

normally expressed in terms of integrity, availability, and confidentiality.

Such factors as the importance of the system to the organization's

mission and the consequences of unauthorized modification, unauthorized

disclosure, or unavailability of the system or data need to be examined

when assessing sensitivity. To address these types of issues, the

people who use or own the system or information should participate

in the assessment.

A sensitivity assessment

should answer the following questions:

- What information is

handled by the system?

- What kind of potential

damage could occur through error, unauthorized disclosure or modification,

or unavailability of data or the system?

- What laws or regulations

affect security (e.g., the Privacy Act or the Fair Trade Practices

Act)?

- To what threats is

the system or information particularly vulnerable?

- Are there significant

environmental considerations (e.g., hazardous location of system)?

- What are the security-relevant

characteristics of the user community (e.g., level of technical

sophistication and training or security clearances)?

- What internal security

standards, regulations, or guidelines apply to this system?

The sensitivity assessment

starts an analysis of security that continues throughout the life

cycle. The assessment helps determine if the project needs special

security oversight, if further analysis is needed before committing

to begin system development (to ensure feasibility at a reasonable

cost), or in rare instances, whether the security requirements are

so strenuous and costly that system development or acquisition will

not be pursued. The sensitivity assessment can be included with

the system initiation documentation either a separate document or

as a section of another planning document. The development of security

features, procedures, and assurances, described in the next section,

builds on the sensitivity assessment.

A sensitivity assessment

can also be performed during the planning stagers of system upgrades

(for either upgrades being procured or developed in house). In this

case, the assessment focuses on the affected areas. If the upgrade

significantly affects the original assessment, steps can be taken

to analyze the impact on the rest of the system. For example, are

new controls needed? Will some controls become necessary?

8.4.2 Development/Acquisition

For most systems, the

development/acquisition phase is more complicated than the initiation

phase. Security activities can be divided into three parts:

- determining

security features, assurances, and operational practices;

- incorporating

these security requirements into design specifications; and

- actually acquiring

them.

These divisions apply

to systems that are designed and built in house, to systems that

are purchased, and to systems developed using a hybrid approach.

During the phase, technical

staff and system sponsors should actively work together to ensure

that the technical designs reflect the system's security needs.

As with development and incorporation of other system requirements,

this process requires an open dialogue between technical staff and

system sponsors. It is important to address security requirements

effectively in synchronization with development of the overall system.

8.4.2.1 Determining

Security Requirements

During the first part

of the development / acquisition phase, system planners define the

requirements of the system. Security requirements should be developed

at the same time. These requirements can be expressed as technical

features (e.g., access controls), assurances (e.g., background checks

for system developers), or operational practices (e.g., awareness

and training). System security requirements, like other system requirements,

are derived from a number of sources including law, policy, applicable

standards and guidelines, functional needs of the system, and cost-benefit

tradeoffs.

Law. Besides specific

laws that place security requirements on information, such as the

Privacy Act of 1974, there are laws, court cases, legal options,

and other similar legal material that may affect security directly

or indirectly.

Policy. As discussed

in Chapter 5, management officials issue several different types

of policy. System security requirements are often derived from issue-specific

policy.

Standards and Guidelines.

International, national, and organizational standards and guidelines

are another source for determining security features, assurances,

and operational practices. Standards and guidelines are often written

in an "if…then" manner (e.g., if the system is encrypting

data, then a particular cryptographic algorithm should be used).

Many organizations specify baseline controls for different types

of systems, such as administrative, mission- or business- critical,

or proprietary. As required, special care should be given to interoperability

standards.

Functional Needs of

the System. The purpose of security is to support the function

of the system, not to undermine it. Therefore, many aspects of the

function of the system will produce related security requirements.

Cost-Benefit Analysis.

When considering security, cost-benefit analysis is done through

risk assessment, which examines the assets, threats, and vulnerabilities

of the system in order to determine the most appropriate, cost-effective

safeguards (that comply with applicable laws, policy, standards,

and the functional needs of the system). Appropriate safeguards

are normally those whose anticipated benefits outweigh their costs.

Benefits and cost include monetary and nonmonetary issues, such

as prevented losses, maintaining an organization's reputation, decreased

user friendliness, or increased system administration.

Risk assessment, like

cost-benefit analysis, is used to support decision-making. It helps

managers select cost-effective safeguards. The extent of the risk

assessment, like that of other cost-benefit analyses, should be

commensurate with the complexity and cost (normally an indicator

of complexity) of the system and the expected benefits of the

assessment. Risk assessment is further discussed n Chapter 7.

Risk assessment can be

performed during the requirements analysis phase of a procurement

or the design phase of a system development cycle. Risk should also

normally be assessed during the development/acquisition phase of

a system upgrade. The risk assessment may be performed once or multiple

times, depending upon the projects methodology.

Care should be taken

in differentiating between security risk assessment and project

risk analysis. Many system development and acquisition projects

analyze the risk of failing to successfully complete the project

- a different activity from security risk assessment.

8.4.2.2 Incorporating

Security Requirements Into Specifications

Determining security

features, assurances, and operational practices can yield significant

security information and often voluminous requirements. This information

needs to be validated, updated, and organized into the detailed

security protection requirements and specifications used by systems

designers or purchasers. Specifications can take on quite different

forms, depending on the methodology used for to develop the system,

or whether the system, or parts of the system, are being purchased

off the shelf.

| Developing

testing specifications early can be critical to being able to

cost-effectively test security features. |

As specifications are

developed, it may be necessary to update initial risk assessments.

A safeguard recommended by the risk assessment could be incompatible

with other requirements or a control may be difficult to implement.

For example, a security requirement that prohibits dial-in access

could prevent employees from checking their e-mail while away from

the office.69

Besides the technical

and operational controls of a system, assurance also should be addressed.

The degree to which assurance (that the security features and practices

can and do work correctly and effectively) is needed should be determined

early. Once the desired level of assurance is determined, it is

necessary to figure out how the system will be tested or reviewed

to determine whether the specifications have been satisfied (to

obtain the desired assurance). This applies to both system developments

and acquisitions. For example, if rigorous assurance is needed,

the ability to test the system or to provide another form of initial

and ongoing assurance needs to be designed into the system or otherwise

provided for. See Chapter 9 for more information.

8.4.2.3 Obtaining the

System and Related Security Activities

During this phase, the

system is actually built or bought. If the system is being built,

security activities may include developing the system's security

aspects, monitoring the development process itself for security

problems, responding to changes, and monitoring threat. Threats

or vulnerabilities that may arise during the development phase include

Trojan horses, incorrect code, poorly functioning development tools,

manipulation of code, and malicious insiders.

If the system is being

acquired off the shelf, security activities may include monitoring

to ensure security is a part of market surveys, contract solicitation

documents, and evaluation of proposed systems. Many systems use

a combination of development and acquisition. In this case, security

activities include both sets.

| In

federal government contracting, it is often useful if personnel

with security expertise participate as members of the source

selection board to help evaluate the security aspects of proposals. |

As the system is built

or bought, choices are made about the system, which can affect security.

These choices include selection of specific off-the-shelf products,

finalizing an architecture, or selecting a processing site or platform.

Additional security analysis will probably be necessary.

In addition to obtaining

the system, operational practices need to be developed. These refer

to human activities that take place around the system such as contingency

planning, awareness and training, and preparing documentation. The

chapters in the Operational Controls section of this handbook discuss

these areas. These areas, like technical specifications, should

be considered from the beginning of the development and acquisition

phase.

8.4.3 Implementation

A separate implementation

phase is not always specified in some life cycle planning efforts.

(It is often incorporated into the end of development and acquisition

or the beginning of operation and maintenance.) However, from a

security point of view, a critical security activity, accreditation,

occurs between development and the start of system operation. The

other activities described in this section, turning on the controls

and testing, are often incorporated at the end of the development/acquisition

phase.

8.4.3.1 Install/Turn-On

Controls

While obvious, this activity

is often overlooked. When acquired, a system often comes with security

features disabled. These need to be enabled and configured. For

many systems this is a complex task requiring significant skills.

Custom-developed systems may also require similar work.

8.4.3.2 Security Testing

System security testing

includes both the testing of the particular parts of the system

that have been developed or acquired and the testing of the entire

system. Security management, physical facilities, personnel, procedures,

the use of commercial or in-house services (such as networking services),

and contingency planning are examples of areas that affect the security

of the entire system, but may be specified outside of the development

or acquisition cycle. Since only items within the development of

acquisition cycle will have been tested during system acceptance

testing, separate tests or reviews may need to be performed for

these additional security elements.

Security certification

is a formal testing of the security safeguards implemented in the

computer system to determine whether they meet applicable requirements

and specifications.70 To provide more

reliable technical information, certification is often performed

by an independent reviewer, rather than by the people who designed

the system.

8.4.3.3 Accreditation

System security accreditation

is the formal authorization by the accrediting (management) official

for system operation and an explicit acceptance of risk. It is usually

supported by a review of the system, including its management, operational,

and technical controls. This review may include a detailed technical

evaluation (such as a Federal Information Processing Standard 102

certification, particularly for complex, critical, or high-risk

systems), security evaluation, risk assessment, audit, or other

such review. If the life cycle process is being used to manage a

project (such as a system upgrade), it is important to recognize

that the accreditation is for the entire system, not just for the

new addition.

|

Sample

Accreditation Statement

In accordance

with (Organization Directive), I hereby issue an accreditation

for (name of system). This accreditation is my formal declaration

that a satisfactory level of operational security is present

and that the system can operate under reasonable risk. This

accreditation is valid for three years. The system will be

re-evaluated annually to determine if changes have occurred

affecting its security.

|

The best way to view

computer security accreditation is as a form of quality control.

It forces managers and technical staff to work together to find

the best fit for security, given technical constraints, operational

constraints, and mission requirements. The accreditation process

obliges managers to make critical decisions regarding the adequacy

of security safeguards. A decision based on reliable information

about the effectiveness of technical and non-technical safeguards

and the residual risk is more likely to be a sound decision.

After deciding on the

acceptability of security safeguards and residual risks, the accrediting

official should issue a formal accreditation statement. While most

flaws in system security are not severe enough to remove an operational

system from service or to prevent a new system from becoming operational,

the flaws may require some restrictions on operation (e.g., limitations

on dial-in access or electronic connections to other organizations).

In some cases, an interim accreditation may be granted, allowing

the system to operate requiring review at the end of the interim

period, presumably after security upgrades have been made.

8.4.4 Operation and

Maintenance

Many security activities

take place during the operational phase of a system's life. In general

these fall into three areas: (1) security operations and administration;

(2) operational assurance; and (3) periodic re-analysis of the security.

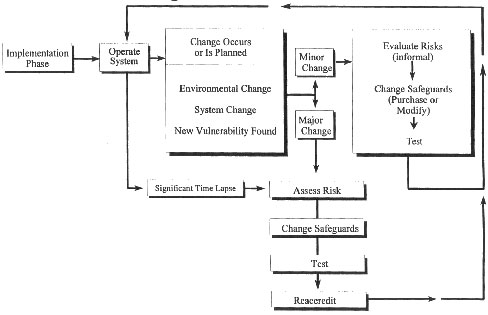

Figure 8.2 diagrams the flow of security activities during the operational

phase.

8.4.4.1 Security Operations

and Administration

Operation of a system

involves many security activities discussed throughout this handbook.

Performing backups, holding training classes, managing cryptographic

keys, keeping up with user administration and access privileges,

and updating security software are some examples.

| Operational

assurance examines whether a system is operated according to

its current security requirements. This includes both the actions

of people who operate or use the system and the functioning

of technical controls. |

8.4.4.2 Operational

Assurance

Security is never

perfect when a system is implemented. In addition, system users

and operators discover new ways to intentionally or unintentionally

bypass or subvert security. Changes in the system or the environment

can create new vulnerabilities. Strict adherence to procedures is

rare over time, and procedures become outdated. Thinking risk is

minimal, users may tend to bypass security measures and procedures.

As shown in Figure 8.2,

changes occur. Operational assurance is one way of becoming aware

of these changes whether they are new vulnerabilities (or old vulnerabilities

that have not been corrected), system changes, or environmental

changes. Operational assurance is the process of reviewing an operational

system to see that security controls, both automated and manual,

are functioning correctly and effectively.

To maintain operational

assurance, organizations use two basic methods: system audits

and monitoring. These terms are used loosely within the computer

security community and often overlap. A system audit is a one-time

or periodic event to evaluate security. Monitoring refers to an

ongoing activity that examines either the system or the users. In

general, the more "real-time" an activity is, the more

it falls into the category of monitoring. (See Chapter 9.)

|

Operational

Phase

During

the operational phase of a system life cycle, major and

minor changes will occur. This figure diagrams appropriate

responses to change to help ensure the continued security

of the system at a level acceptable to the accrediting official.

Figure

8.2

|

8.4.4.3 Managing Change

| Security

change management helps develop new security requirements. |

Computer systems and

the environments in which they operate change continually. In response

to various events such as user complaints, availability of new features

and services, or the discovery of new threats and vulnerabilities,

system managers and users modify the system and incorporate new

features, new procedures, and software updates.

The environment in which

the system operates also changes. Networking and interconnections

tend to increase. A new user group may be added, possibly external

groups or anonymous groups. New threats may emerge, such as increases

in network intrusions or the spread of personal computer viruses.

If the system has a configuration control board or other structure

to manage technical system changes, a security specialist can be

assigned to the board to make determinations about whether (and

if so, how) changes will affect security.

Security should also

be considered during system upgrades (and other planned changes)

and in determining the impact of unplanned changes. As shown in

Figure 8.2, when a change occurs or is planned, a determination

is made whether the change is major or minor. A major change, such

as reengineering the structure of the system, significantly affects

the system. Major changes often involve the purchase of new hardware,

software, or services or the development of new software modules.

An organization does

not need to have a specific cutoff for major-minor change decisions.

A sliding scale between the two can be implemented by using a combination

of the following methods:

- Major change.

A major change requires analysis to determine security requirements.

The process described above can be used, although the analysis

may focus only on the area(s) in which the change has occurred

or will occur. If the original analysis and system changes have

been documented throughout the life cycle, the analysis will normally

be much easier. Since these changes result in significant system

acquisitions, development work, or changes in policy, the system

should be reaccredited to ensure that the residual risk is still

acceptable.

- Minor change.

Many of the changes made to a system do not require the extensive

analysis performed for major changes, but do require some analysis.

Each change can involve a limited risk assessment that weighs

the pros (benefits) and cons (costs) and that can even be performed

on-the-fly at meetings. Even if the analysis is conducted informally,

decisions should still be appropriately documented. This process

recognizes that even "small" decisions should be risk-based.

8.4.4.4 Periodic Reaccreditation

Periodically, it is useful

to formally reexamine the security of a system from a wider perspective.

The analysis, which leads to reaccredidation, should address such

questions as: Is the security still sufficient? Are major changes

needed?

| It

is important to consider legal requirements for records retention

when disposing of computer systems. For federal systems, system

management officials should consult with their agency office

responsible for retaining and archiving federal records. |

The reaccredidation should

address high-level security and management concerns as well as the

implementation of the security. It is not always necessary to perform

a new risk assessment or certification in conjunction with the re-accreditation,

but the activities support each other (and both need be performed

periodically). The more extensive system changes have been, the

more extensive the analyses should be (e.g., a risk assessment or

re-certification). A risk assessment is likely to uncover security

concerns that result in system changes. After the system has been

changed, it may need testing (including certification). Management

then reaccredits the system for continued operation if the risk

is acceptable.

8.4.5 Disposal

|

Media

Sanitization

Since

electronic information is easy to copy and transmit, information

that is sensitive to disclosure often needs to be controlled

throughout the computer system life cycle so that managers

can ensure its proper disposition. The removal of information

from a storage medium (such as a hard disk or tape) is called

sanitization. Different kinds of sanitization provide

different levels of protection. A distinction can be made

between clearing information (rendering it unrecoverable by

keyboard attack) and purging (rendering information unrecoverable

against laboratory attack). There are three general methods

of purging media: overwriting, degaussing (for magnetic media

only), and destruction.

|

The disposal phase of

the computer system life cycle involves the disposition of information,

hardware, and software. Information may be moved to another system,

archived, discarded, or destroyed. When archiving information, consider

the method for retrieving the information in the future. The technology

used to create the records may not be readily available in the future.

Hardware and software

can be sold, given away, or discarded. There is rarely a need to

destroy hardware, except for some storage media containing confidential

information that cannot be sanitized without destruction. The disposition

of software needs to be in keeping with its license or other agreements

with the developer, if applicable. Some licenses are site-specific

or contain other agreements that prevent the software from being

transferred.

Measures may also have

to be taken for the future use of data that has been encrypted,

such as taking appropriate steps to ensure the secure long-term

storage of cryptographic keys.

8.5 Interdependencies

Like many management

controls, life cycle planning relies upon other controls. Three

closely linked control areas are policy, assurance, and risk management.

Policy. The development

of system-specific policy is an integral part of determining the

security requirements.

Assurance. Good

life cycle management provides assurance that security is appropriately

considered in system design and operation.

Risk Management.

The maintenance of security throughout the operational phase of

a system is a process of risk management: analyzing risk, reducing

risk, and monitoring safeguards. Risk assessment is a critical element

in designing the security of systems and in reaccreditations.

8.6 Cost Considerations

Security is a factor

throughout the life cycle of a system. Sometimes security choices

are made by default, without anyone analyzing why choices are made;

sometimes security choices are made carefully, based on analysis.

The first case is likely to result in a system with poor security

that is susceptible to many types of loss. In the second case, the

cost of life cycle management should be much smaller than

the losses avoided. The major cost considerations for life cycle

management are personnel costs and some delays as the system progresses

through the life cycle for completing analyses and reviews and obtaining

management approvals.

It is possible to overmanage

a system: to spend more time planning, designing, and analyzing

risk than is necessary. Planning, by itself, does not further the

mission or business of an organization. Therefore, while security

life cycle management can yield significant benefits, the effort

should be commensurate with the system's size, complexity, and sensitivity

and the risks associated with the system. In general, the higher

the value of the system, the newer the system's architecture, technologies,

and practices, and the worse the impact if the system security fails,

the more effort should be spent on life cycle management.

References

Communications

Security Establishment. A Framework for Security Risk Management

in Information Technology Systems. Canada.

Dykman,

Charlene A. ed., and Charles K. Davis, asc. ed. Control Objectives

-- Controls in an Information Systems Environment: Objectives, Guidelines,

and Audit Procedures. (Fourth edition). Carol Stream, IL: The

EDP Auditors Foundation, Inc., April 1992.

Guttman, Barbara. Computer

Security Considerations in Federal Procurements: A Guide for Procurement

Initiators, Contracting Officers, and Computer Security Officials.

Special Publication 800-4. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute

of Standards and Technology, March 1992.

Institute of Internal

Auditors Research Foundation. System Auditability and Control

Report. Altamonte Springs, FL: The Institute of Internal Auditors,

1991.

Murphy, Michael, and

Xenia Ley Parker. Handbook of EDP Auditing, especially Chapter

2 "The Auditing Profession," and Chapter 3, "The

EDP Auditing Profession." Boston, MA: Warren, Gorham &

Lamont, 1989.

National Bureau of Standards.

Guideline for Computer Security Certification and Accreditation.

Federal Information Processing Standard Publication 102. September

1983.

National Institute of

Standards and Technology. "Disposition of Sensitive Automated

Information." Computer Systems Laboratory Bulletin. October

1992.

National Institute of

Standards and Technology. "Sensitivity of Information."

Computer Systems Laboratory Bulletin. November 1992.

Office of Management

and Budget. "Guidance for Preparation of Security Plans for

Federal Computer Systems That Contain Sensitive Information."

OMB Bulletin 90-08. 1990.

Ruthberg, Zella G, Bonnie

T. Fisher and John W. Lainhart IV. System Development Auditor.

Oxford, England: Elsevier Advanced Technology, 1991.

Ruthberg, Z., et al.

Guide to Auditing for Controls and Security: A System Development

Life Cycle Approach. Special Publication 500-153. Gaithersburg,

MD: National Institute of Standards. April 1988.

Vickers Benzel, T. C.

Developing Trusted Systems Using DOD-STD-2167A. Oakland,

CA: IEEE Computer Society Press, 1990.

Wood,

C. "Building Security Into Your System Reduces the Risk of

a Breach." LAN Times, 10(3), 1993. p 47.

Footnotes:

65.

A computer system refers to a collection of processes, hardware,

and software that perform a function. This includes applications,

networks, or support systems.

66.

Although this chapter addresses a life cycle process that starts

with system initiation, the process can be initiated at any point

in the life cycle.

67.

An organization will typically have many computer security plans.

However, it is not necessary that a separate and distinct plan exist

for every physical system (e.g., PCs). Plans may address, for example,

the computing resources within an operational element, a major application,

or a group of similar systems (either technologically or functionally).

68.

For brevity and because of the uniqueness of each system, none of

these discussions can include the details of all possible security

activities at any particular life cycle phase.

69.

This is an example of a risk-based decision.

70.

Some federal agencies use a broader definition of the term certification

to refer to security reviews or evaluations, formal or information,

that take place prior to and are used to support accreditation.

|